As we have previously discussed, Miranda Warnings are only required when someone is in custody and subject to interrogation. An interrogation refers to direct questioning by police after a suspect has been taken into custody. The Supreme Court ruled as much in 1980 after Thomas Innis, a man who had been arrested for robbing a taxi driver at gunpoint, ended up leading his arresting officers to the gun he used in his crimes. He did this after hearing two officers discuss their concern for mentally disabled children in the area who might find the gun and hurt themselves. The Supreme Court ruled that the shotgun was admissible in court because Innis’s statement had been spontaneous, and was not technically the product of “interrogation.” Remember, voluntary statements are admissible.

No matter how serious the crime, you are protected by your Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination and your Sixth Amendment right to counsel. Anyone who is in custody and being questioned should specifically invoke your rights. Unless you explicitly say that you are invoking your right to remain silent, you might not actually be exercising it, the Supreme Court ruled in its controversial 2010 decision in a case called Berghuis, Warden v. Thompkins. The defendant, Van Chester Thompkins, was interrogated by police for three hours without saying a word. Towards the end of the interrogation, when asked if he prayed to God to forgive him for the shooting he was suspected of, he answered, “Yes.” The majority ruled that his offhanded confession was unprotected by Miranda. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, dissenting, remarked that the court had concluded “that a suspect who wishes to guard his right to remain silent … must, counterintuitively, speak.”

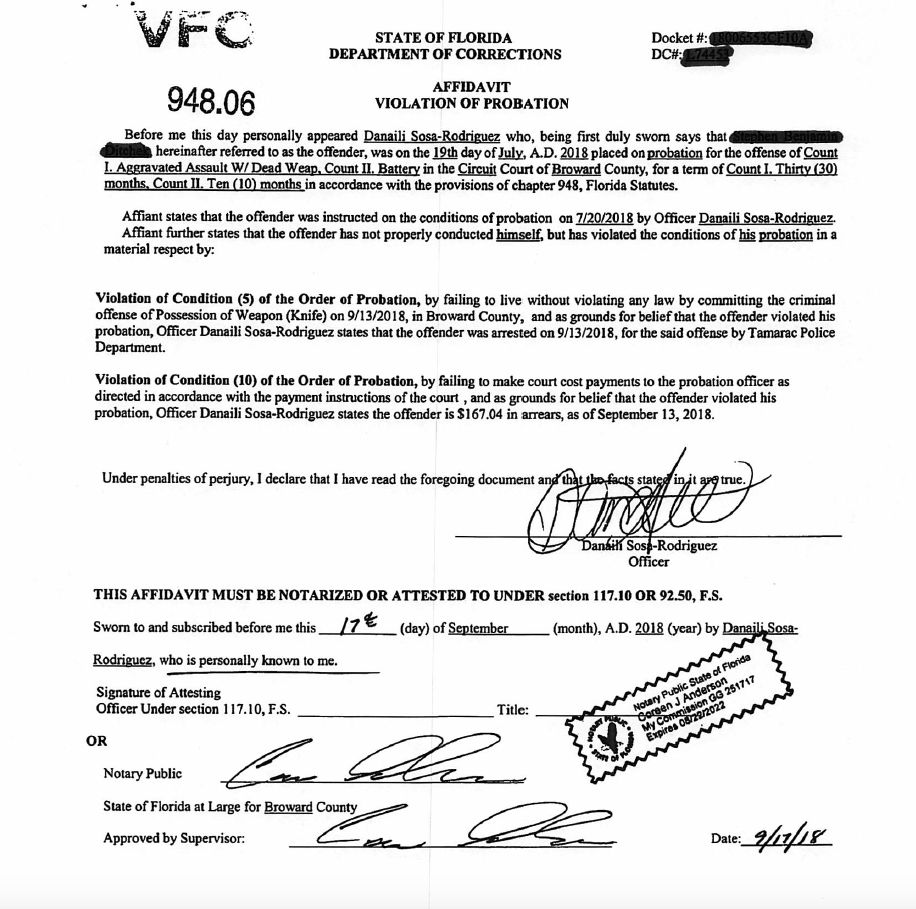

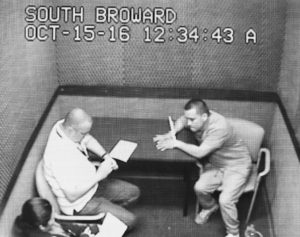

So here is an example of a recent case involving a waiver of the Miranda warnings. At the beginning of the interrogation, the following exchange took place:

Officer: So I want to go over your Miranda warnings. That means you have the right to remain silent, okay?

A: Uh-huh.

Q: Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law.

A: Uh-huh.

Q: You have the right to talk to a lawyer and have him or her present with you while you’re being questioned.

A: Uh-huh.

Q: Okay. If you cannot afford to hire a lawyer, one will be appointed to represent you before any further questioning, if you wish. If you decide to answer questions now, without your lawyer being present, you have the right to change your mind at any time and request a lawyer be present before any further questioning. So if you don’t like the way it’s going, you can say, whoa, [detective].

A: I don’t have no lawyer, so —

Q: You — –

A: I don’t even have no money to call a lawyer.

Q: Okay. But, understand, you know, you could have one, but — do you have any questions about these? Do you understand them?

A: Uh-huh.

Q: You do? Do you understand the rights? Could I get an initial right there? And if you want to talk to me now. (emphasis added).

Too often people waive their rights to remain silent and have an attorney present. Once the Miranda warnings are read and then waived, then the interrogator uses his training and expertise to illicit incriminating statements that are recorded and will be used later in trial. In the scenario above, the Defendant waived his rights and admitted to committing the crimes charged. Luckily for this Defendant, the Miranda warnings were captured on video.

A Motion to Suppress was filed and argued to the Court because the waiver of his Miranda rights (“I don’t have no lawyer, so — I don’t even have no money to call a lawyer.”) was ambiguous. The Courts have held that the Interrogator has a duty to clarify that there is a knowing and intelligent waiver. “[A]n ambiguous waiver must be clarified before initial questioning.” Alvarez v. State, 15 So. 3d at 745. “Prior to obtaining an unambiguous and unequivocal waiver, a duty rests with the interrogating officer to clarify any ambiguity before beginning general interrogation.” U.S. v. Rodriguez, 518 F. 3d 1072, 1080 (9th Cir. 2008) (considering waiver of right to remain silent when officer inquired if suspect “wished to speak to him” and suspect responded “I’m good for tonight.”). See also Miles v. State, 60 So. 3d 447, 451 (Fla. 1st DCA 2011) (“If the suspect makes an equivocal request to remain silent before waiving his Miranda rights, the police must clarify the suspect’s intent before continuing the interrogation.”)

Even if an interrogation has begun and you have answered some questions, you can stop the questioning by telling police that you are exercising your right to stay silent.

If you or a loved one has been arrested and you believe the police violated your Miranda rights, contact Broward Criminal Defense Attorney Neil C. Kerch for a free initial case consultation.

Disclaimer:

This post is only general information and is not legal advice or a substitute for legal advice. You should only use this post to familiarize yourself with the criminal justice process in Florida. Importantly, each case is unique and will not necessarily be handled in the same manner as described in this post. Please contact Neil C. Kerch for a free initial case consultation if you have specific questions regarding your involvement with the criminal justice system.

Criminal Defense attorney Broward County

Miranda Warnings Broward County

Criminal Defense attorney Miami-Dade County

Miranda Warnings Miami-Dade County

Criminal Defense attorney Palm Beach County

Miranda Warnings Palm Beach County